The Mozilla Platform is a large software development tool that is a modern blend of XML document processing, scripting languages, and software objects. It is used to create interactive, user-focused applications. This book is a conceptual overview, reference, and tutorial on the use of the platform for building such applications.

The Mozilla Platform encourages a particular style of software development: rapid application development (RAD). RAD occurs when programmers base their applications-to-be on a powerful development tool that contains much pre-existing functionality. With such a tool, a great deal can be done very quickly. The Mozilla Platform is such a tool.

One strategy for doing RAD is to make sophisticated HTML pages and display them in a Web browser. This book does not explain HTML, nor does it show how to create such pages. It has very little to do with HTML. Instead, it shows how to create applications that require no browser, and that might appear to be nothing like a Web browser. Such applications might be Web-enabled, benefiting from the advantages that Web browsers have, or they might have nothing to do with the Web at all.

Because Mozilla is closely linked to the Web in people's minds, this last point cannot be emphasized enough. The Mozilla Platform is far more than a browser. Here are some statistics:

- Mozilla contains well over 1,000 object types and well over 1,000 interfaces.

- It is highly standards compliant, supporting many standards from bodies such as the W3C, IETF, and ECMA. These bodies are, respectively, the World Wide Web Consortium, the Internet Engineering Task Force, and the European Computer Manufacturers' Association.

- Mozilla is built on a very big source code base and is far larger than most Open Source projects. It is 30 times larger than the Apache Web Server, 20 times larger than the Java 1.0 JDK/JRE sources, 5 times bigger than the standard Perl distribution, twice as big as the Linux kernel source, and nearly as large as the whole GNOME 2.0 desktop source — even when 150 standard GNOME applications are included.

- As a result of the browser wars in the late 1990s, the platform has been heavily tested and is highly optimized and very portable. Not only have hundreds of Netscape employees and thousands of volunteers worked on it, but millions of end users who have adopted Mozilla-based products have scrutinized it as well.

This extensive and tested set of features is a huge creative opportunity for any developer interested in building applications. These features also offer an opportunity for traditional Web developers to broaden their existing skills in a natural way.

This book covers the Mozilla Platform up to version 1.4. Changes between minor versions (e.g., 1.3 and 1.4) are small enough that most of this book will be correct for some time.

Useful Knowledge

Some experience is required when reading this book. Some familiarity with Web standards is assumed. This list of skills is more than enough preparation:

- A little HTML or XHTML

- A little XML

- A little JavaScript, or another scripting language, or one of the C languages (C, C++, C#, Java, IDL)

- A little CSS2

- A little Web page development

- A little SQL

- A little experience working with objects

- The pleasure of having read the W3C's DOM 2 Core standard at least once

All the standards for these technologies, except SQL and JavaScript, are available at www.w3.org.

To read this book with very little effort, add these skills: a little Dynamic HTML; a little Prolog; more experience with an object-brokering system like COM or CORBA; additional experience with another RAD tool like a 4GL or a GUI Designer; and more SQL experience.

It is common for advanced Mozilla programmers to have a full copy of the Mozilla Platform source code (40 MB, approximately). This book sticks strictly to the application services provided by the platform. There is no need to get involved in the source code, unless that is your particular interest.

The Structure of This Book

Chapter 1, Fundamental Concepts, is an overview of Mozilla. The remaining chapters mimic the structure of the Mozilla Platform. The early chapters are about the front part of Mozilla, comprising XML markup, which displays the elements of a graphical user interface. As the chapters proceed, the subject matter works its way to the back of Mozilla. The back consists of objects that silently connect to other computing infrastructure, like file systems, networks, and servers. To summarize:

- Chapter 1 is a concept overview.

- Chapters 2, 3, and 4 describe basic XUL markup. XUL is a dialect of XML.

- Chapter 5 explains the JavaScript language.

- Chapters 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 describe interactions between the DOM, JavaScript, and XUL.

- Chapter 11 explains the RDF data format.

- Chapters 12, 13, and 14 describe interactions between XUL and RDF.

- Chapter 15 explains how to enhance XUL using XBL.

- Chapter 16 describes many useful XPCOM objects. XPCOM is Mozilla's component technology.

- Chapter 17 describes how to deploy a finished application.

Within this flow from front to back, each chapter follows a set structure:

- Facing the start of each chapter is a special diagram called the NPA diagram.

- The first few paragraphs of a chapter introduce the chapter concepts, expanding on brief remarks in Chapter 1, Fundamental Concepts. Read these remarks to identify whether the chapter is relevant to your need.

- For more difficult material, these concepts are expanded into a concept tutorial. Read this tutorial material when looking through the book for the first time, or if a concept seems very foreign.

- Next, all the technical detail is laid out in a structured manner. Many examples are provided to support a first-time read, but this detail is designed to be flipped through and revisited later when you've forgotten something.

- In later chapters, this reference material is followed by a scripting section that explains what JavaScript interactions are possible. Read this when XUL and RDF alone are not enough for your purposes.

- "Style Options" describes the impact of the CSS standards on the chapter. Read this when a window doesn't look right.

- "Hands On" contains the NoteTaker tutorial that runs throughout the book. Read this when you need to get into the coding groove.

- "Debug Corner" contains problem-solving advice and collected wisdom on the chapter's technology. Read this before coding and when you're really stuck.

- Finally, the summary closes with a reflective overview and exits gracefully in the direction of the next chapter.

Some of these structural elements are discussed in the following topics.

The NPA Diagram

The core of the Mozilla Platform is implemented in the C and C++ programming languages, using many object classes. To understand how it all works, one could draw a huge diagram that shows all the object-oriented relationships explicit in those classes. Such a diagram would be quite detailed, and any high-level features of the platform might not be obvious. Although the diagram might be accurate, it would be a challenge to understand.

The NPA diagram is a simplified view of Mozilla's insides. NPA stands for not perfectly accurate. It is a learning aid. No one is arguing that Mozilla is built exactly as the diagram shows; the diagram is just a handy thinking tool. There is no attempt to illustrate everything that Mozilla does.

The NPA diagram appears prior to each chapter of this book. The subject matter of a given chapter is usually tied to a specific part or parts of the diagram.

Style Options

Mozilla makes extensive use of cascading stylesheet styles. In addition to features described in the CSS2 standard, Mozilla has many specialist style extensions. An example of a Mozilla-specific style is

vbox { -moz-box-orient: vertical; }

Most chapters contain a short section that describes Mozilla-style extensions relevant to that chapter.

The NoteTaker Tool

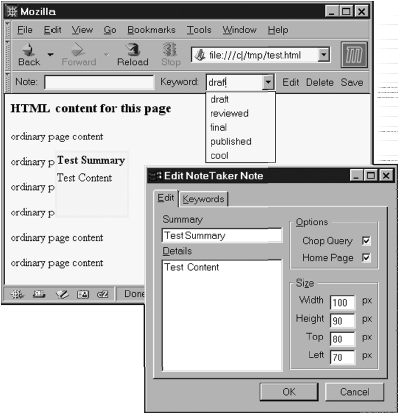

NoteTaker is a small programming project that is a running example throughout this book. There isn't room for developing a full application, so the compromise is a small tool that is an add-on. NoteTaker is a Web browser enhancement that provides a way to attach reminder notes (Web notes) to displayed Web pages. The browser user can attach notes to the pages of a Web site, and when that Web site is visited at a later date, the note reappears. This is done without modifying the remote Web site at all. Notes can be created, edited, updated, and deleted.

The browser window shown has a new toolbar, which is the NoteTaker toolbar. That toolbar includes a drop-down menu, among other things. The displayed HTML page includes a small pale rectangle — that is the Web note for the page's URL. That rectangle does not appear anywhere in the displayed test.html file. Also shown is the Edit dialog window, which is used to specify the content and arrangement of the current note.

As an idea, it doesn't matter whether NoteTaker is pure genius or horribly clumsy. Its purpose is to be a working technology demonstrator. Each chapter enhances NoteTaker in a small way so that, by the end of this book, all Mozilla's technologies can be seen at work together.

There is no generally agreed upon technical term for describing NoteTaker. The relationship between the tool and a browser is a little like the relationship between a Java applet and a Java application. It is an add-on that is more than a mere configuration option but less than a plugin.

This example project is attached to a Web browser. Generally speaking, Mozilla applications should run in their own windows with no Web browser in sight. There is no implication that all Mozilla applications should be designed like NoteTaker — it is just that NoteTaker is too small as described here to stand by itself.

Hands On: Tools Needed for Development

Even this short introduction attempts to follow the chapter structure described earlier. To begin development with Mozilla, you need a computer, software, and documentation.

Microsoft Windows, Macintosh, and UNIX/Linux are all acceptable development systems, although Mac OS 9 support is slowly being dropped and perhaps should be avoided. The computer does not need to be Internet-enabled or even LAN-enabled after the platform is installed. The Mozilla Web site, www.mozilla.org, is the place to find software. Chapter 1, Fundamental Concepts, discusses software installation in "Hands On."

The sole warning in this introduction relates to documentation. This book alone is simply not enough information for all development needs. It would need to be a 10-volume encyclopedia to achieve that end. Just as UNIX has man(1) pages and applications have help systems, Mozilla has its own electronic reference information. That information complements the material in this book.

Unfortunately, that help information is widely scattered about and must be collected together by hand. Here are the documents you should collect while you are downloading a copy of the platform:

- From the W3C, www.w3.org, download all of these standards: CSS2, CSS2.1, XML 1.0, XHTML 1.0, DOM 1 all parts, DOM 2 all parts, DOM 3 all parts, and RDF. These standards are nearly all available in high-quality PDF files and can be viewed electronically with the free Adobe Acrobat Reader (at www.adobe.com). The CSS2, DOM 2 Core, and DOM 2 Events standards are the most important ones; the others are rarely needed.

- From ECMA, www.ecma-international.org, download the ECMA-262 ECMAScript standard. This is the JavaScript standard. You can do without it, but it is occasionally handy.

- From Prentice Hall's Web site, http://authors.phptr.com/mcfarlane/, or from the author's Web site, www.nigelmcfarlane.com, download sets of XPIDL interface files. These definition files describe all the object interfaces in Mozilla. These files are extracted from the source code and bundled up for your convenience.

- Also from http://authors.phptr.com/mcfarlane/ or from www.nigelmcfarlane.com, download class-interface reports. These specially prepared files are a nearly accurate list of the class-interface pairs supported by the platform. These lists help answer the question: What object might I use? They can be manipulated with a text editor or a spreadsheet.

- Finally, it would be helpful to possess a Web development book with a JavaScript focus.

If you are very detail oriented and have copious free time, then you might consider adding a full copy of the Mozilla Platform source code (40 MB approximately). That is not strictly required.

It is common for advanced application programmers to retain a full copy of the Mozilla Platform source code (40 MB, approximately). This book sticks strictly to the application services provided by the platform, so there is no need to get involved in the source code, unless that is your particular interest.

Debug Corner: Unreadable Documentation

Make sure that any documentation you download has the right format for your platform. The UNIX tools unix2dos and dos2unix can help; also UNIX files can be read on Microsoft Windows with any decent text editor (e.g., gvim at www.vim.org).

The font system on Linux is sometimes less than adequate and can make PDF text hard to read. To fix this, follow the suggestions in the Mozilla release notes. For other font problems, see the discussion on fonts in Chapter 3, Static Content.

Some standards are written in HTML. If you save these files to local disk and disconnect from the Internet, sometimes they display in a browser very slowly. This is because the browser is trying to retrieve stylesheets from a Web server. To fix this, choose "Work Offline" from the File menu, and reload the document.

Summary

Mozilla is a massively featured development environment with origins in XML, objects, and the Web, and application developers can easily exploit it. I hope you enjoy reading this book as much as I enjoyed writing it. I wish you many constructive and creative hours exploring the technology, should you choose to take it up. With that said, here we go...